When it comes to our life and decisions, we’re optimistic rationalizers. Every New Year’s Eve, we take resolutions that are grounded in perfectly valid reasons – reducing weight, quitting cigarettes, reading more books and so on. If someone asks why we want to read books, we can confidently blurt out that it will expand our worldview.

Fast-forward a couple of weeks in the new year, and we’re often back to our old ways. It’s spectacular that even when we quit our yearly resolution within weeks, we always have good reasons for why we abandoned our goals. (We’d rarely acknowledge that we’re lazy or are addicted to cigarettes.)

This tendency of people to provide well-thought-out reasons to justify their behavior easily misleads entrepreneurs who go around asking “if I build this, will you buy it?”.

If you put people under the spotlight of this question, they will say something that makes sense. Nobody wants to appear to be a fool. However, the key question is if they’ll act the same way too when you’re not around.

Asking people to justify their purchases or to imagine whether they will make a specific purchase is a useless exercise. If someone has purchased a TV of a specific brand, and you ask them why they purchased it, you’ll likely get a battery of reasons. People want to appear rational decision makers, so they will cite price, quality, technology or other dimensions as criteria. However, the truth may be that it was an impulse purchase because of a discount during a trip to a mall.

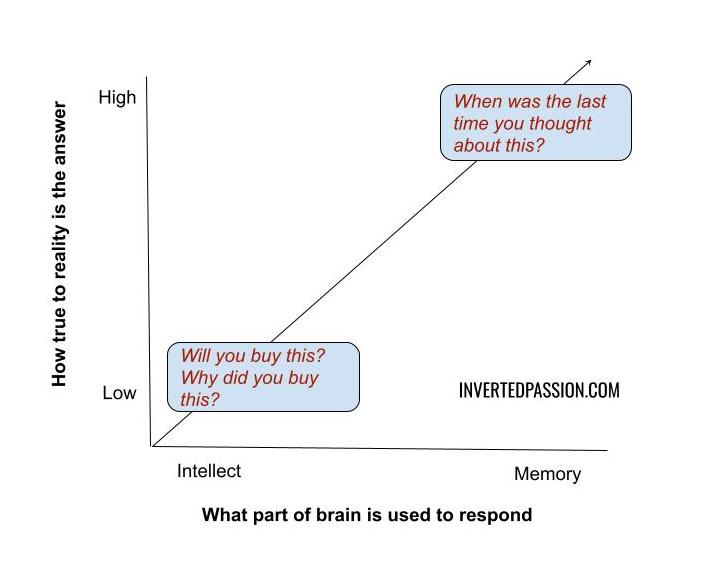

Actually, it’s not like people lie on purpose. Rather, our brains have evolved to supply justifications for our actions. So asking someone to rely on reasoning and intellect is a sure shot way of getting fabricated answers.

Rather than asking people to use their imagination, a much better way to interview is to probe their actual past behavior. That way, you’re more likely to get a truer picture of how they behave (smoking several cigarettes every day) rather than getting reasons for how they want to behave (quitting the habit).

People say all sorts of things to comfort themselves and others while they go on about doing something else. As an entrepreneur, you’re interested in what they actually do, not what they say.

If someone is truly interested in quitting cigarettes, you’ll see this in their behavior when you probe and nudge them about their attempts to quit. If it is their burning desire to quit cigarettes, and they haven’t been able to do it, they will remember many such attempts with clarity. In contrast, if quitting is just someone’s idle desire, they’ll fumble and not clearly remember when was the last time they seriously attempted quitting cigarettes.

A practical tip on orienting people to rely on their memory:

Ask them to imagine a documentary being shot on their life, and they have to remember as many details about the sequence of events leading to a specific event (like purchase of a competitive product).

Get as many details from them as possible – who all were involved in the purchase decision, where they were when the thought first came to their mind, who did they talk to about their decision, how did they start the search and so on.

Ensure that you’re not guiding their answers by asking leading questions. Your job during an interview is to listen impartially. Be careful of nudging people subtly towards answers that you desire. That’s confirmation bias at play, and you’d be doing it without realizing.

It’s true that one interview doesn’t reveal much. But as you interview multiple people, you will start observing repeated patterns. (Perhaps you will realize that in your industry, people are much more driven than impulse than you imagined). Such repeated patterns are the real nuggets of insights about people’s true desires.

Yes, there’s a risk in relying on memories too, as people can fabricate false memories without realizing that something they remembered never happened. However, the probability of a false memory is much less than the probability of a false reason.

Remember: words are cheap and people use them liberally. Actions are where the truth lies, and the only way to get access to people’s actions is to ask them to remember what they did, and not why they did.

This essay is part of my book on mental models for startup founders.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra