End customers typically get value through a series of businesses adding value on top of each other. For example, imagine the value chain required to bring a laptop to the end customer. The production begins with suppliers of metals and raw materials which are used by computer part manufacturers to build components like CPU, screens, and disk drives. These components are then assembled to build a laptop. The laptop needs software that’s typically written by some other supplier like Microsoft. And, finally, the fully functional, ready-to-use laptop is shipped by a logistics company to a warehouse. Customers transact with an online or offline seller of laptops which is typically yet another company (Amazon or BestBuy).

The entire value chain of a laptop comprises different businesses at different stages who all compete for a share of the $1000 price of the laptop.

The key question is who gets what share of this $1000?

The question is important because all businesses in the value chain want to maximize their share of this money but only a few are able to do so. To maximize their share of the money, all businesses try to squeeze their upstream suppliers in terms of cost and squeeze their downstream customers in terms of price. Gradually, few players in the value chain emerge as the ones who’re in the commanding position to set prices for others and everyone else has to adjust their profit margins to accommodate their asks.

How do you think Apple boasts of >50% margin for their phones while LG exited the mobile phone business altogether citing profitability concerns?

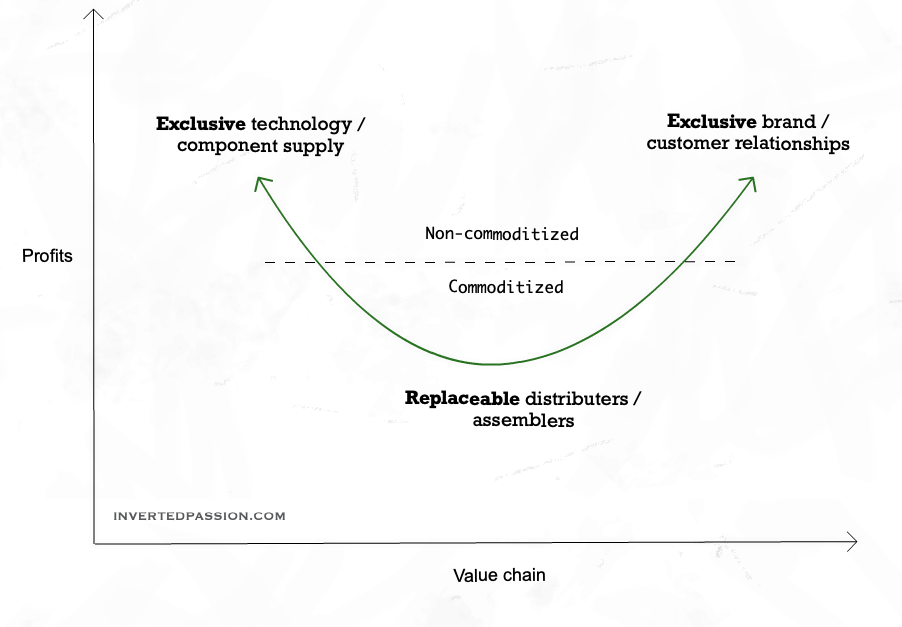

Often, businesses that have either exclusive intellectual property or exclusive customer relationships end up commoditizing other businesses in the value chain. As a thumb rule, if a business is irreplaceable, it will eat profits of another upstream or downstream business that’s undifferentiated. In fact, what suggests differentiation is not an entrepreneur’s opinion but a healthy profit margin on the balance sheet.

For example, in the laptop industry, companies like Intel, ARM and Nvidia supply processors and graphics chips that are built on top of their patented intellectual property. There aren’t many alternatives to microprocessor companies but there are many suppliers of metals that go into building these chips and many assemblers who use these chips to assemble computers (Lenovo, Acer, Compaq, DELL, etc.). Similarly, because laptop users are familiar with Microsoft Windows and many of their apps only run on Windows, Microsoft is in a position to dictate their own price, which computer assemblers have to pay out of the money they get from the customer. Hence, in this simplified example of the laptop industry, profits accumulate at companies that are irreplaceable. Rest of the businesses in the value chain end up struggling to make profits because competition between them drives down the money they can keep for themselves.

Another example of this is the evolving online news industry. Before Facebook or Twitter came along, people used to visit individual publication’s website (like NYTimes.com or CNN.com). These publications owned the relationship with the customers, and hence accumulated the profits while commoditizing its suppliers (the journalists on their payroll). Now with Facebook and Twitter becoming the primary mode of discovering and consuming news for many people, these publications are getting commoditized.

The surprising thing is that because of this commodification of publications, journalists who have a knack for writing content that catches attention on Facebook or Twitter are getting de-commoditized (Substack, I’m looking at you!). Social media has reduced publications to assemblers and elevated good journalists as exclusive suppliers. Some publications tried rebelling against this process by removing themselves from Facebook but they quickly came back as they realized that Facebook now owns customer relationships as customers weren’t abandoning it anytime soon.

While genuine, non-competitive partnerships exist and you must try creating them, most businesses try to continuously squeeze other businesses wherever they can. So, an entrepreneur must always try to be unique and irreplaceable, while exploring alternatives for its downstream and upstream businesses to reduce dependence on them.

Remember: profits accumulate to the one who’s irreplaceable.

This essay is part of my book on mental models for startup founders.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra