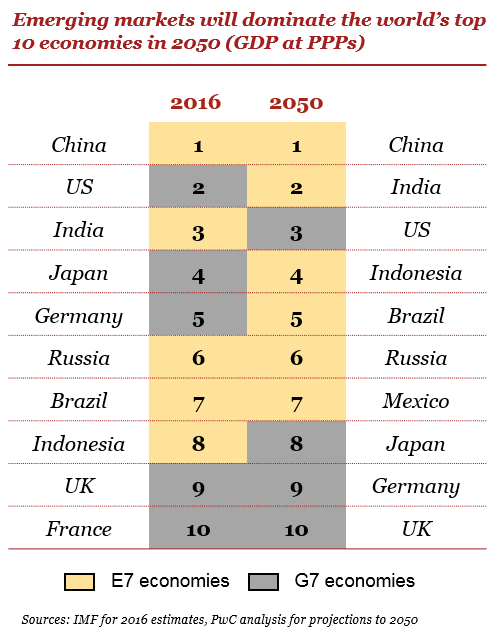

Making predictions about future is more than a fun past time. Gartner, Forrester, and many other research companies justify their existence by predicting where technology industry is going. Other organizations (like PwC, below) once in a while go crazy and release predictions decades ahead of now.

Such long-range predictions are ironic because we can’t even get short-range predictions right. For example, from this news report:

While projecting a more optimistic picture of the global economy, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Tuesday slashed India’s growth forecast by 0.5 percentage points to 6.7 percent in 2017.

Of course, IMF didn’t see the banning of major currency notes (demonetization) in India and its second and third order consequences in the economy (to their credit, neither did Modi). IMF actually admits their blindness.

The growth projection for 2017 has been revised down… reflecting still lingering disruptions associated with the currency exchange initiative introduced in November 2016, as well as transition costs related to the launch of the national Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July 2017,” it said in its October 2017 World Economic Outlook.

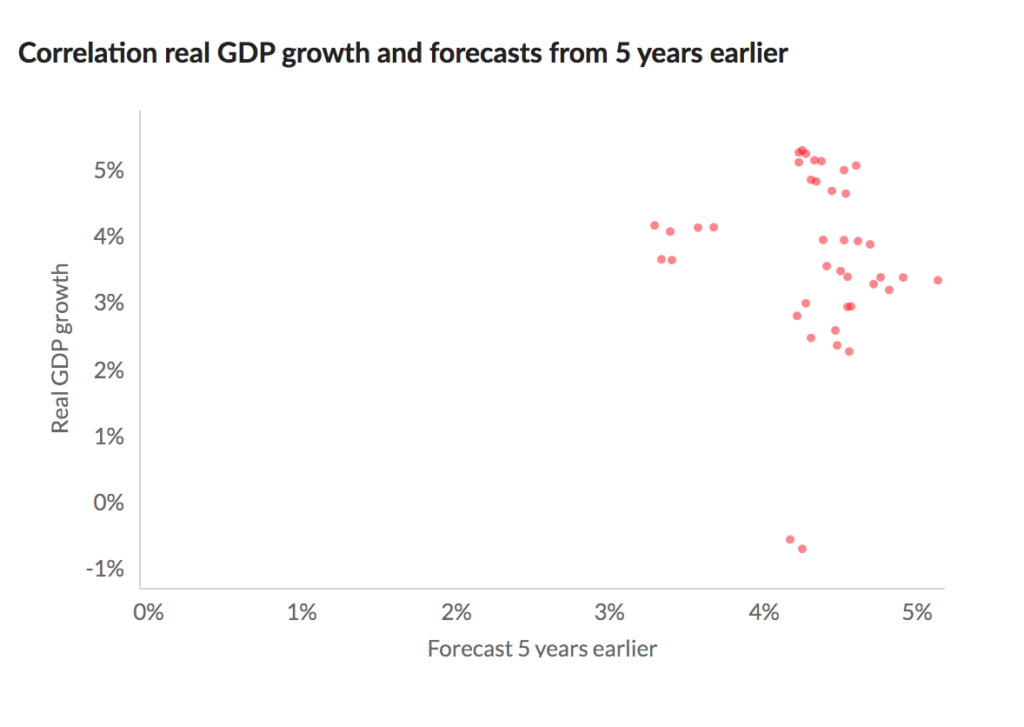

If you compare how their five-year world GDP growth predictions did with actual world GDP growth, this is the scatter plot you get.

It’s laughably uncorrelated and so the entire yearly effort of making predictions is a big waste of money, time and attention. With regards to economic predictions, the magazine Economist notes that “since economic output represents the aggregated activity of billions of people, influenced by forces seen and unseen, it is a wonder forecasters ever get it right”. That’s exactly right.

It’s just not black swan events

Nasim Taleb made famous the notoriously hard to predict “black swan” events such as 2008 US housing crisis or 2016 demonetization in India. However, the issue of prediction isn’t just about these wild unexpected events. Predicting future is difficult because of multiple reasons:

- Individual humans are free-willed, and that makes the behavior of an aggregate of humans (say a nation, an industry) probabilistic (rather than deterministic).

- Human systems are openly interacting. With all feedback loops and non-linear relationships, it is an impossible task to model how these numerous openly interacting human systems impact each other. (See my previous post on “wicked problems“).

- The environment keeps on changing alongside and we fail to accommodate that in our predictions. When we make a prediction about something, we’re focused on it specifically and ignore the larger context. This focus on a specific prediction (say GDP growth rate) makes us rely more upon variables immediately related to the predicted variable and exclude seemingly unrelated variables. For example, because we have to predict GDP, we will include foreign investment inflow as a variable but likely exclude a model of free speech (and thousands of other “irrelevant” variables). If a forecaster doesn’t model free speech in China’s GDP projection, and a major shift in political environment happens there, his predictions are screwed (because these two variables are indeed related). Next year, he will include free speech but miss on other uncountably many factors.

Accurate predictions are impossibly hard because while we’re focused on the predicted quantity, we only include immediately related variables, and generally ignore the environment. Psychologists call this bias focalism and it’s also responsible for people overestimating the impact of bad events in their lives. While a person is (justifiably) focused on how bad losing his legs in an accident will be, he will forget that Netflix, tasty dinners, friends and ice cream will remain there to provide him with happiness.

Predictions gone wrong

When people in 1800s were asked to predict how year 2000 will look like, they got it horribly wrong.

Of course, they could not have predicted the atomic bomb, the drones, and the cyber warfare. They were focused on taking their then current technologies: cars and guns to imagine a future where these will get combined.

Similarly, I think we could be totally missing the mark on how currently hyped-up technologies (such as AI and blockchain) will change the world. Will blockchain disrupt governments and promote free borders? Maybe. It’s hard to predict. The Atlantic thinks it may very well promote even further authoritarianism. Which way it’ll go, I really do not know and hence wouldn’t bet my life savings on (more on this later).

Self fulfilling and self-defeating prophecies

Moore’s law is famous for accurately predicting that every two years the number of transistors that can be packed in a given area will double. That law was a self-fulfilling prophecy because Intel’s engineers were incentivized to not make their founder look like a fool. So they worked hard to make the prediction come true, year after year. Similarly, the Indian government is incentivized to make its own economic growth promises come true. This suggests a good thumb rule to know which predictions will come true: whenever you see a prediction, see who made the prediction and think how much is the predictor vested to make it come true and does s/he have abilities and power to do so.

On the flip side, there are predictions that incentivize people to not make them true. This is what makes unemployment and poverty predictions notoriously inaccurate – they’re self-defeating prophecies. Hence, the study of actors who make predictions and their incentives is as important as analyzing the method and logic of predictions.

How to live in a world that resists predictions

Whether we like it or not, in business and life, we have to constantly plan for future. With the understanding that future resists accurate predictions, I suggest following guidelines.

Don’t bet your life on future. Only bet what you can afford to lose. (This guides how we plan for future at Wingify).

Plan for worst-case scenario. Even doing nothing is a prediction. If you get an unexpected slap in the future, you should be able to recover from it. This means saving regularly, having a separate reserve of money for bad times, and paying for health insurance.

If you must, bet on what is NOT likely to change. People will always be dissatisfied with their current options, governments will never give up power with ease, and businesses will always want to maximise profits.

Wait for favorable opportunities to show up in the environment and then pounce hard. Till then, keep a lookout for such opportunities without losing heart or your life’s savings.

What things will NOT change in next 10 years?

Now that you’ve read the article, I have a related question for you and I think it’ll give your neurons a good cardio.

People have fun predicting how things will change. Let’s flip it. What are the things that will NOT change in next 10 years?

I’ll RT interesting answers.

— Paras Chopra (@paraschopra) December 15, 2017

What do you think will remain same in next 10 years? Tweet your response to me as a reply to this thread and I’ll retweet the most interesting responses. In the same thread, you can also check out and comment on what others proposed.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra