The first book I ever read was The Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking. I liked it so much that I re-read it 8 times. As a young boy, the book had made a lasting impression on me, making me fall in love with ideas such as the arrow of time, black holes, entropy, and Big Bang. Reading this book, you can’t help but open up to the spirit of science that pushes you to keep exploring the boundaries of knowledge, one hypothesis at a time.

I am very much a product of such thinking process. In fact, during one of my sabbaticals, I took up the goal to understand all of currently unsolved problems in physics. This required me to brush up on quantum mechanics, general relativity, cosmology, and standard model. It took some serious effort, but in the end, I’m glad I was able to rise up beyond the pop-science level of understanding of physics. By the end of my sabbatical, I was finally able to look at quantum mechanics equations and understand what they were about.

If you’ve ever fallen into such a physics rabbit hole, you start suspecting that everything is reducible to physics. The urge of grand unification is strong when you read books written by physicists for popular consumption (such as The Big Picture) that attempt to explain everything in the universe. Note that it’s always physicists who write such “grand” sweeping books but you’d never see a chemist or botanist do the same.

Grand Unified Theories cannot exist

Two books that I read recently provided me useful perspectives on how the step-by-step reductive view of the world is limited, and, relatedly, why we shouldn’t expect a theory or an algorithm that explains it all.

Both of these books make different points, but the ideas felt connected to me. (Yep, I recognize the irony!)

In the book Mathematica, David talks about the primacy of intuition in doing mathematics. He makes a persuasive case about how mathematical ability – which he defines as being able to visualize abstractions – is like all other abilities and can be developed over time. Just like you’d practice your backhand to improve tennis, he says you can practice visualizing mathematical problems until they become obvious to you.

He recommends against starting with logic. He said that professional mathematicians glimpse “truths” intuitively and only then use step-by-step logic in order to prove what they know to be true.

The book was eye-opening for me because I always assumed that the computational procedure of exploring logical consequences of axioms is how math is done. But, no, David said it’s the other way around, which makes sense because logic cannot guide where to go next.

Logic cannot create, it only verifies creations that arise in our brain.

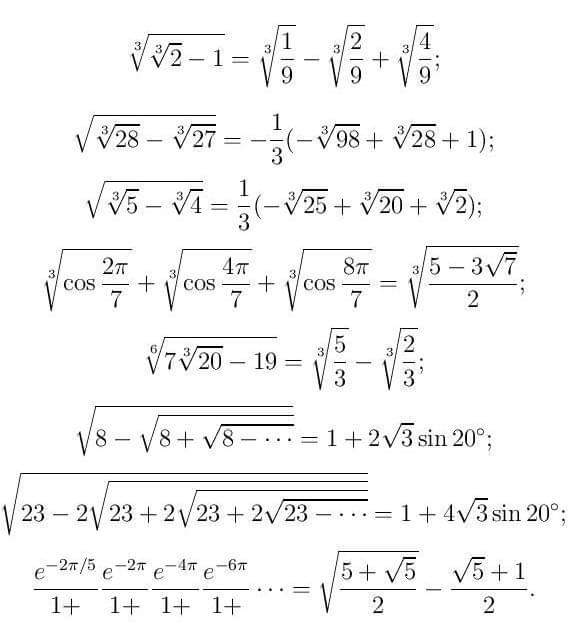

In the last chapter, David cites the example of the great Indian mathematician Ramanujan who wrote highly non-trivial formulas without any proof at all. Ramanujan said these proofs were given by a Goddess in his dreams. It’s fascinating that most of his formulas have later turned out to be true when other mathematicians gave logical proofs of such formulas.

How do you explain Ramanujan’s “magical” abilities? His process was highly non-logical, and demands an explanation that doesn’t seem easily reducible to physics. Yes, of course, you can claim that brain is made up of neurons, which in turn are made up of fundamental particles, so somewhere the explanation might exist but we don’t just know it yet. But would this be an explanation or simply a mirage of an explanation?

We couldn’t glimpse into Ramanujan’s brain, but we could do so for ChatGPT. Even though all the code and weights of GPT style models are available to anyone to introspect, we still don’t fully understand how language models work in terms of its elementary operations of matrix multiplications. The wonder of how a bunch of matrix multiplications lead to LLMs is similar to the wonder of how a bunch of neurons lead to Ramanujan.

In terms of coming up with mathematical formulas, there’s something that clearly Ramanujan was doing, not his neurons, and not his electrons that make up those neurons. Ramanujan is an entity in itself, and while some parts are reducible to physics under some circumstances, it’s a mistake to say Ramanujan is a pattern of fundamental particles. The pattern is the key entity worth studying. In this case, fundamental particles are actually uninteresting and incidental.

So, it’s clear that the domain of Ramanujan is different than the domain of neuroscience, which in turn is different than the domain of the standard model. All this might seem obvious, but it’s worth stressing upon because the idea that everything reduces to physics ultimately leads to bizarre conclusions such self not existing, consciousness being an illusion, life being devoid of meaning, or the disenchantment with the world because everything is “just” atoms buzzing around.

World is Universe++

The other book Why the World Does Not Exist gave me a fresh perspective on why science is one domain among many. The author Markus differentiates between universe (the place where we find physical “stuff”) and the world (universe + domain of ideas). It’s easy to see that our world contains ideas, even though our universe does not. Harry Potter really does exist in the world created by J K Rowling. That world, in fact, impacts our universe by making kids line up in front of stores whenever a new book is being released. So anyone who claims that Harry Potter doesn’t exist is really saying a fact about the universe, but not about the world.

Similarly to the world of Harry Potter, the world of morality exists, which cannot be reduced to the world of standard model (with particles and forces between them). The world of math is different. So is the world of India’s independence movement. All these worlds exist and are as real as the world of fundamental particles and forces. Moreover, all these worlds have concrete effects on our universe. So, even though the worlds are imaginary, their effects are real. Hence, ignoring these worlds as non-consequential is a big mistake.

Also notice how these worlds aren’t necessarily connected with each other. While humans have an insane drive to see grand unifications everywhere, our world doesn’t oblige. The world of hip-hop dancing is not connected in any meaningful way to the world of Viking history. Yes, we can sometimes open up thin wormhole connections between different worlds, but many worlds exist disconnected from other worlds in any meaningful way (and that’s ok!).

Truth is contextual

Recently, I’ve also been delving into symbolic AI, which led me to the Cyc project. It was a multi-decade attempt to bake-in hundreds of thousands of common sense “facts” into a logical system to be able to answer any question by tracing its logical consequences. The hypothesis was that once you bake in what we know to be true (like dogs are mammals), we can have software do reasoning equivalent to a child.

This project of building a unified, connected web of logical statements was compelling (and still is!). But when you read this retrospective by Cyc’s founder, you’ll see that Cyc team pivoted from their initial approach very soon after launching when they realized that a general purpose reasoning algorithm probably doesn’t exist.

The Cyc team fell into reduce-everything-to-fundamentals trap, but the business needs to provide a workable solution pushed them to recover from it. Instead of one unified web of logical statements, they started developing thousands of micro-domains – each with its own web of facts and a customized reasoning engine. This change of architecture allowed them to do context-dependent reasoning. So, when someone asks: “are doctors good?”. The answer depends on the context. (And often it is usefulness of the answer that determines whether we adopt it as true or not.)

Solving equations requires a different domain knowledge than answering questions of morality. So, it isn’t a good idea to reduce everything to “fundamentals”. Such reduction doesn’t guarantee universality of problem-solving. In fact, each domain of interest requires its own battery of tools.

Infinite worlds imply infinite meanings

Physics to me is the claim that everything can be explained in terms of fundamental “stuff” in the universe and the forces + interactions between them. Physics is very useful for certain problems, but is absolutely useless in other domains.

I think it’s a beautiful fact that so many different worlds exist beyond our physical universe, each with its own sets of objects and relationships between them. Also, it’s liberating to realize that any hierarchy of sciences or fields of study is entirely hypothetical. Physics is not necessarily more “fundamental” than other sciences. Take the example of micro-processors. Sure, you can explain how a chip works via electrons and their quantum tunneling. But, a complete explanation of micro-processor requires ideas from many other domains – how capital is organized for big projects such as fabs, how intellectual property is prevented, metallurgy, software, geopolitics and so on. This begs the question – why single out physics as the base layer?

What about reality?

As I said earlier, I’ve been long obsessed with exploring fundamental questions of reality. Questions such as why does the universe exist or what is consciousness made of have charmed me ever since I started asking questions. Deep down, I have always wanted a neat, compact, single explanation of reality – one sentence explanation for everything.

But, gradually, it’s dawning upon me that this drive might be misguided. What if the world is not like a small ball but instead is like a big city with different areas, each having its own vibe?

What if it’s worthwhile to study consciousness under its own terms and not in terms of fundamental particles? What if the meaning of life (the singular) is instead meanings of life (the plural)? What if humanities is as worthwhile a subject as the sciences?

Reality being a disjoint collection of domains seems infinitely more rich than it being a single equation.

Not everything is physics, nor it needs to be.

TLDR

If you go look for meaning in the universe of fundamental “lifeless” particles, you won’t find it.

But if you look for meaning in the world that’s much bigger and richer than the universe, you will find it everywhere!

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra