I was talking to a friend who has subscribed to an online publication called The Ken. This subscription costs him around Rs. 2000 per year and he gets access to hundreds of exclusive in-depth, well-researched articles on Indian startups. I asked him if he’ll renew, and he said probably not as he didn’t think that he got worth his money from the 15-20 articles that he had read. This conversation was happening at a bar where the average bill per person comes to be about Rs. 1500. I pointed this to him and we wondered why he was willing to pay Rs 1500 for a 3-hour sitdown at a bar but doesn’t find it worth Rs 2000 to read 15-20 well research articles.

What was happening here?

Humans are not utility maximizers

The most common form of pricing advice is to price a product or a service as a percentage of value it creates for the customer. It’s called value-based pricing and its irresistible logic is hard to escape. Isn’t it obvious that if a product creates a value of 100 units for me, a customer should be willing to pay anything below 100 units to have it?

Value-based pricing is a good advice in a universe where customers are rational and logical. But this universe isn’t that one. Upon encountering a price, customers do not morph into a computer to come up with an accurate measure of utility that they expect to derive from the product. Rather, they feel in their gut whether a price is fair or not.

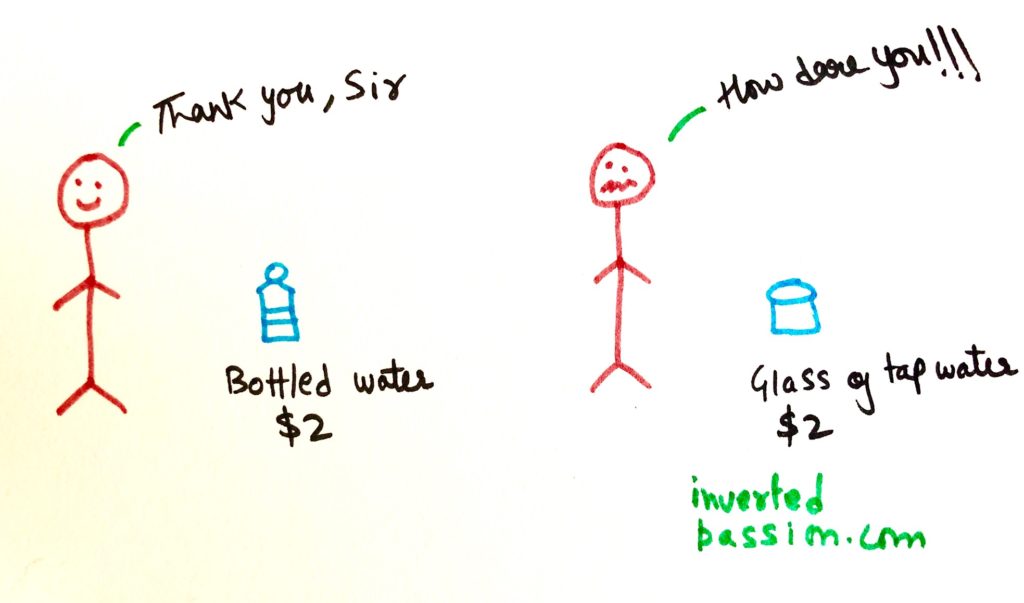

Customers decide on an acceptable price based on whether it seems fair, and not based on the amount of value they’ll derive from it. There’s a famous experiment in behavioral economics that illustrates this. It’s called Thaler’s Beer Experiment (there are two scenarios, with one of them in brackets).

You are lying on the beach on a hot day. All you have to drink is ice water. For the last hour you have been thinking about how much you would enjoy a nice cold bottle of your favorite brand of beer. A companion gets up to go make a phone call and offers to bring back a beer from the only nearby place where beer is sold (a fancy resort hotel) [a small, run-down grocery store]. He says that the beer might be expensive and so asks how much you are willing to pay for the beer. He says that he will buy the beer if it costs as much or less than the price you state. But if it costs more than the price you state he will not buy it. You trust your friend, and there is no possibility of bargaining with (the bartender) [store owner]. What price do you tell him?

Before reading further, make your own estimates for these two scenarios.

The results reported in the original paper (for which Richard Thaler won Nobel Prize this year!) was as follows: the median price given in the fancy resort hotel version was $2.65 while the median for the small run-down grocery store version was $1.50. This experiment has been repeated many times and results always show a difference in two scenarios. Note that the utility respondents derive from both scenarios is exactly same. The only difference is what seemed like a “fair” price for these two scenarios.

In a value maximization world, customers should be OK paying the same amount for either scenario. But our world is different. Here on Earth, in addition to getting a positive utility from products, customers also want to make sure they get a “fair” deal. It’s as if customers are willing to ignore all the value they could have gotten from a product if they feel the seller is taking an unfair advantage of the situation. (For an interesting discussion on this, see this thread on Tripadvisor where a shocked customer is discussing whether it was fair for a restaurant in Austria to charge him for tap water).

Where does this “fair” price come from?

Customers form expectations of the price for a product based on their previous encounters of price for the same product or its competitors. While growing up, we see our parents pay for things (like cable, milk, eggs, rent, etc.) and because we see our parents pay them, those prices become reference prices for “fairness” and as prices evolve, so do our expectations of them. But if they go up suddenly, there’s a mismatch and we find the increased prices unfair. For example, as a kid, I used to buy milk from the market every day and the price I paid then (about Rs. 15 per liter) became my reference price for milk. I’ve not been buying milk for a long time, so recently when I came across the price of milk, I was shocked and horrified. (It is about Rs 50 per liter) But many of my friends did not share my shock. For them, this price was OK because they’ve been buying their own milk and have seen it evolve over time. Note that I shouldn’t have been shocked if I was valuing milk according to the utility I’d get from it. I was shocked because there was a mismatch between my internal reference price and the market price.

The more recent an experience with a price, higher the influence it has on my estimate of the fair price. This suggests that prices are always constrained by the history of prices of similar products and there’s little one particular company can do to change it singlehandedly. This explains why customers get pissed off by a sudden increase in prices even with the extra value provided with that increase. No matter how many billions Netflix pours in producing new content, they simply aren’t allowed to raise prices by two dollars.

But because customers find a price increase unfair does not necessarily mean it’s a bad business strategy. In fact, the real test of a business is if it’s able to increase prices without losing customers. Netflix raised their prices from $7.99 to $9.99, pissed off their customers but very few canceled because there is no decent competitive service. However, this luxury can only be had after success. Not a good idea for startups.

How are innovative products or services priced?

While analyzing an innovative product, customers draw parallels with a historically familiar category or subcategory and then make sense of the unfamiliar product. This is both a problem and an opportunity.

It’s a problem because the historical category that customers compare the innovative product with might not be a good representation of its potential value. This problem happened with one of the products we were experimenting with at Wingify. The service was called in3bullets and to our users, we sent daily summaries of long-form articles. We launched a beta and users loved it. We had open rates of 40%+ for the newsletter and we regularly got feedback telling us how reading in3bullets became a daily habit for many people. All good signs. Yet when announced our intention to charge for the service, very few beta users were ready to pay for it. This was a surprise because we had solid evidence that we were creating a positive utility every day for our users. But for our users, the only fair price for such a service was zero. Internet has habituated people to get information for free and we alone could not change that.

A similar issue happened with another of our new product experiments. It was a digital art frame (called Maya) that you could hang on your wall and it’ll download and show a new piece of art every day. Many beta users took it home and liked it a lot but then they asked: “how is it different from a monitor with a slideshow”?

Slowly it became clear that the products we were building created economic value for the customer but because we left their positioning unaddressed, customers automatically compared it with they knew from previous experience (newsletters = free; something that shows images = monitor, so their reference prices came from such comparisons.)

These two were missed opportunities because research suggests that for innovative products or services, customers get heavily influenced by the suggested categories and so the marketer has a big influence on whether it’ll succeed or fail. This is why the first automobile was called a horseless carriage.

I find it interesting that for really innovative products that are truly groundbreaking (say Napster, Internet, Operating System), decisions on how they’re positioned has a significant influence on its economic success or failure. On the flip side, this linkage of new products with existing products in customers’ minds restricts the freedom a company has in setting prices. Remember: the environment shapes customers expectations of what is a fair price. If customers have started to expect information or news for free, there’s very little an individual company can do to change that perception. But what if we had positioned it as a research service? (A company, of course, can participate in an industry-wide shift where customers gradually become familiar with paywalls everywhere and their internal reference prices rise.)

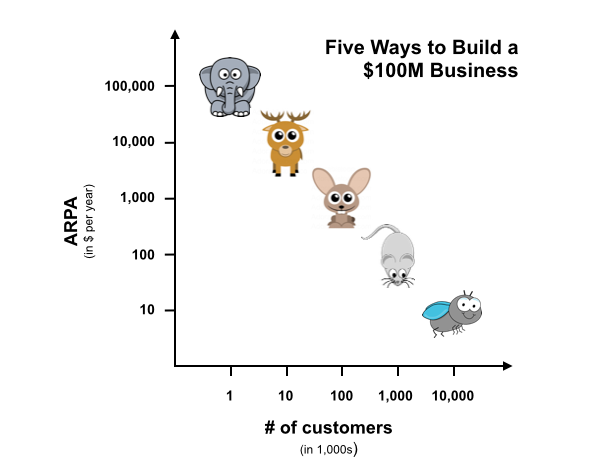

Price selects the market in B2B

It is generally assumed that buyers are rational in the B2B world. Business customers see how much money a service is generating or saving and they pay a percentage of it. Because business decisions usually involve multiple people, it is true that they’re less emotional and that calculation of ROI is easier. But that doesn’t mean purchase decisions are rational. For business customers, expectations of value and price they’re willing to pay also come from their previous experiences. In fact, for B2B products or services, customers use the price to shortlist products or services.

I’ll give an example. Pricing for VWO (Wingify’s first product) started from $49/mo and the highest plan we showed on the website was $249/mo. By doing this, we were telling the customer that we’re meant for mid-sized businesses. Even though our product created value for enterprises and small businesses, we were excluding them because that’s a price these two types of customers weren’t familiar with in their previous purchases. Economic theory suggests that if an enterprise comes across $49/mo service that generates 100x value, it’s a steal but in my experience enterprises do not for cheap products because the price means the product isn’t for them.

With our mid-market pricing, our customers had slotted us in an existing category of SaaS purchases. If we had priced $0 (free), we would have asked them to categorize ourselves with products meant for very small businesses that did something very simple. If we had priced ourselves as $5000/mo, we would have set their expectation to be dealt with a salesperson who visits their office and a dedicated account manager they can call any time.

I find it amazing that for the same product, pricing gives an entrepreneur the freedom to select different markets. Pricing is a great lever for creating profits out of thin air.

How you position a product determines the acceptable price for it. (Is it luxury? Mass market? Enterprise? SMB? Similar to some other popular product?) And there’s magic in getting the price right. The customer ends up feeling getting a fair deal from you and you end up getting good profit for your efforts.

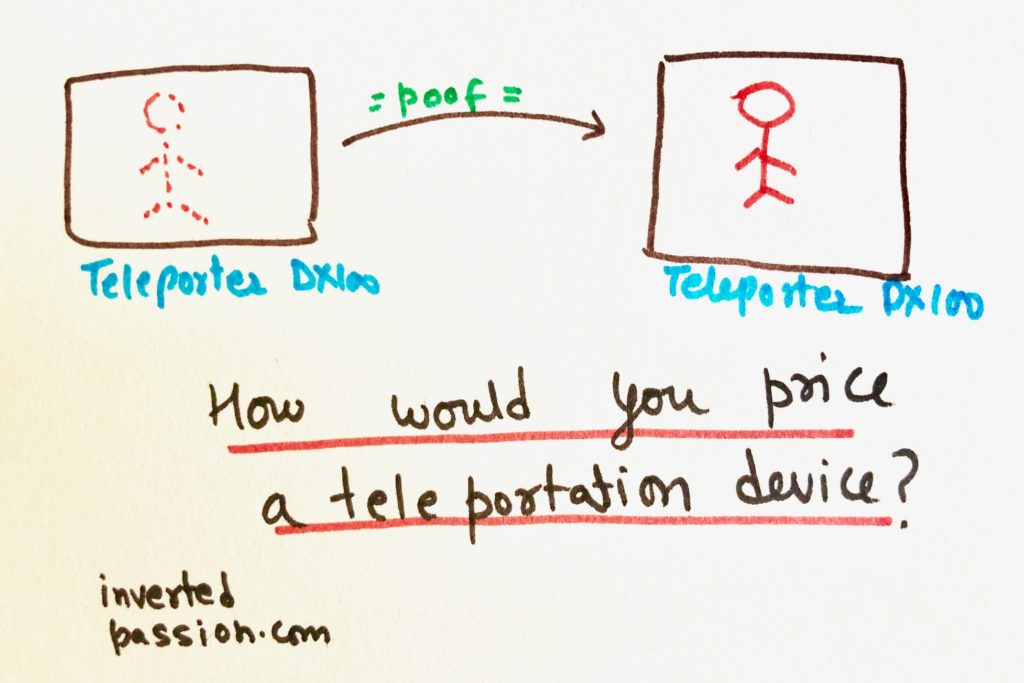

The Teleporter DX100

Now that you’ve read the article, I have a question for you.

How would you price a teleportation device whose cost of production and operation is similar to a microwave? This device can teleport a person or stuff to any place in the universe.

I'll RT interesting suggestions.

— Paras Chopra (@paraschopra) December 24, 2017

How would you price this revolutionary device? It’s a fun and challenging exercise. Tweet your response to me as a reply to this thread and I’ll retweet the most interesting responses. In the same thread, you can also check out and comment on what others proposed.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra