Fundraising is an exercise in demonstrating how your company can generate financial returns for the investor.

Different types of investors have different risk-reward expectations and that’s why they end up specializing. For example, a bank as an institution is risk-averse. They’re okay with a relatively smaller return (marginally more than the risk-free return) but they want to make sure that such return is guaranteed.

On the other hand, funds specializing in seed-stage funding know that most of their investments will fail, and hence to cover for those duds, they expect to fund only the opportunities which can generate 100x returns. The few 100x returning opportunities and most of the others not returning anything means that on average they end up generating a decent financial return on their entire fund.

Not understanding the motivation of an investor class is a sure-shot way of an unsuccessful fundraise. Pitching to a bank that you’re building a great product is likely a waste of time. They want their guaranteed 10% return and it’s immaterial whether you generate that return via a great product or by selling bread.

On the other hand, talking about how profitable and safe your business is to a VC is likely to be a waste of time because it signals that your business is already peaked and the 100x return that a VC expects won’t come via your company. If a VC wanted safe 10% returns, a VC would open up a bank. VCs exist for providing a different kind of capital – a type of capital that cannot be had from banks.

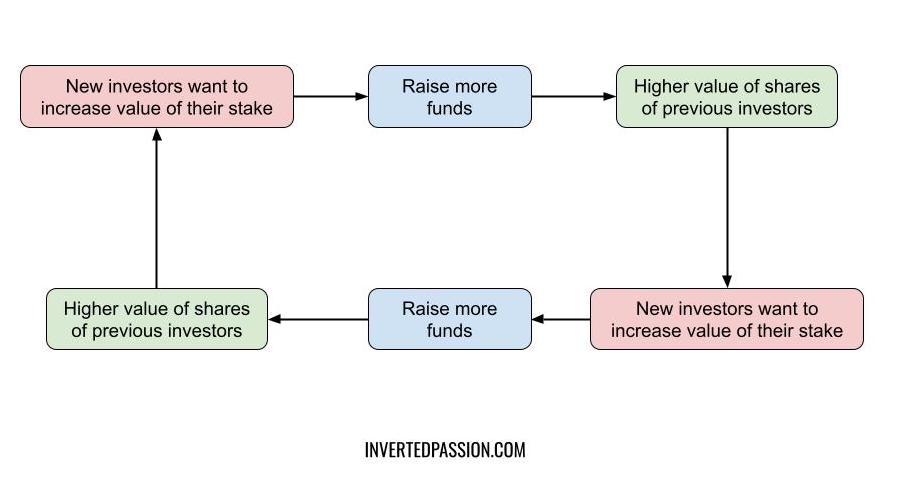

There’s a logical reason why unprofitable companies get funded. It’s because unprofitable companies, by definition, have to raise more funds in the future. And with each funding round, the expectation is that the funding would happen at a higher valuation at the next round, thereby increasing the value of the stakes purchased by investors. And of course, the new investors expect to make money from future rounds of funding. This is why companies don’t raise funds for safety or survival and keep them in their banks. VCs expect the raised funds to be spent within 12-18 months so that another round is raised soon, and with it, the value of their shares goes up. The end game of VC-led funding rounds is a company IPOing and eventually letting retail investors buy shares from initial investors at a premium.

All this means that to raise funds from VCs, the company has to show a path to becoming big enough to IPO. For VCs, a great product, a good team, and good business fundamentals are important but secondary considerations. The primary one is whether a particular business can keep on raising funds until it goes public or becomes important enough to be acquired.

Remember: understand what drives VCs and then decide whether you’re ready to commit your company to that path. If the answer is yes, the entire focus of the funding pitch must be on opportunity size and growth potential because that’s what matters to VCs.

This essay is part of my book on mental models for startup founders.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra