It’s in the news today. Ola, India’s largest on-demand taxi service, has acquired FoodPanda India (from its parent company Delivery Hero) in a stock-swap transaction. FoodPanda is in food delivery business (like GrubHub in US or Delivery Hero in Europe).

Ola’s Founder and CEO said the usual acquisition-related things in a press release.

I’m excited about our partnership with Delivery Hero as we team up to take Foodpanda India to the next level. As one of India’s pioneers in the food delivery space, Foodpanda has come to be a very efficient and profit focused business over the last couple of years. Our commitment to invest $200mn in Foodpanda India will help the business be focused on growth by creating value for customers and partners. With Delivery Hero’s global leadership and Ola’s platform capabilities with unique local insights, this partnership is born out of strength.

Notice the title of company’s press release: “Ola and Delivery Hero join forces in India”. It doesn’t even mention the name of the business that’s exchanging hands.

Online food delivery business has negative unit economics. With average order value of Rs. 300 or so, the commission per order food delivery companies get is in the range of Rs 45-60 (15%-20%). On the cost side, they need to pay Rs. 60-75 to food delivery boys. Clearly, the online food delivery is an unprofitable business; with every delivery, these companies lose Rs 10-20. (All these numbers + more sourced from this analysis).

Sp why is Ola (and many others like Uber, Google, Amazon) interested in this massively unprofitable online food delivery business in India? The answer may lie in the opportunity for online food delivery companies to do with restaurants what Netflix has done to movie studios.

The old way

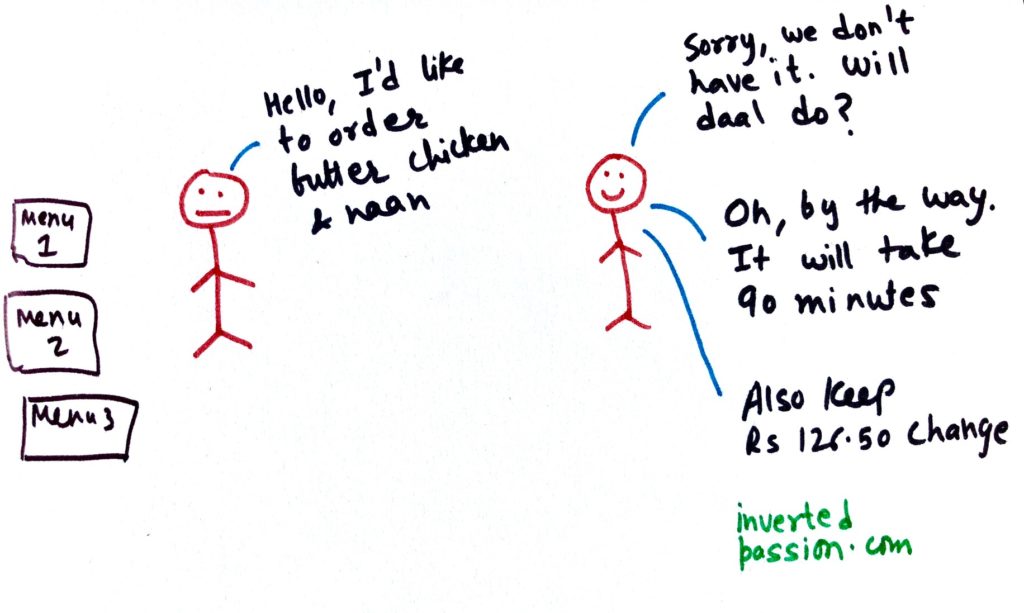

Before online food delivery started, people ordered food by calling the restaurant.

This process had many inefficiencies:

- You had to store and organize multiple physical menus

- You had limited options (how many menus can you really store in your house?)

- There was no guarantee that the restaurant will pick up your phone

- It took time and effort to call, say your order and then confirm it

- You had no idea how much time the order will take to get delivered

- Delivery took ages because delivery person usually didn’t have any incentive to hasten the order

- If you get the wrong order, there was nothing you could do about it

- You had to find exact amount of cash to give to the delivery person

The new way

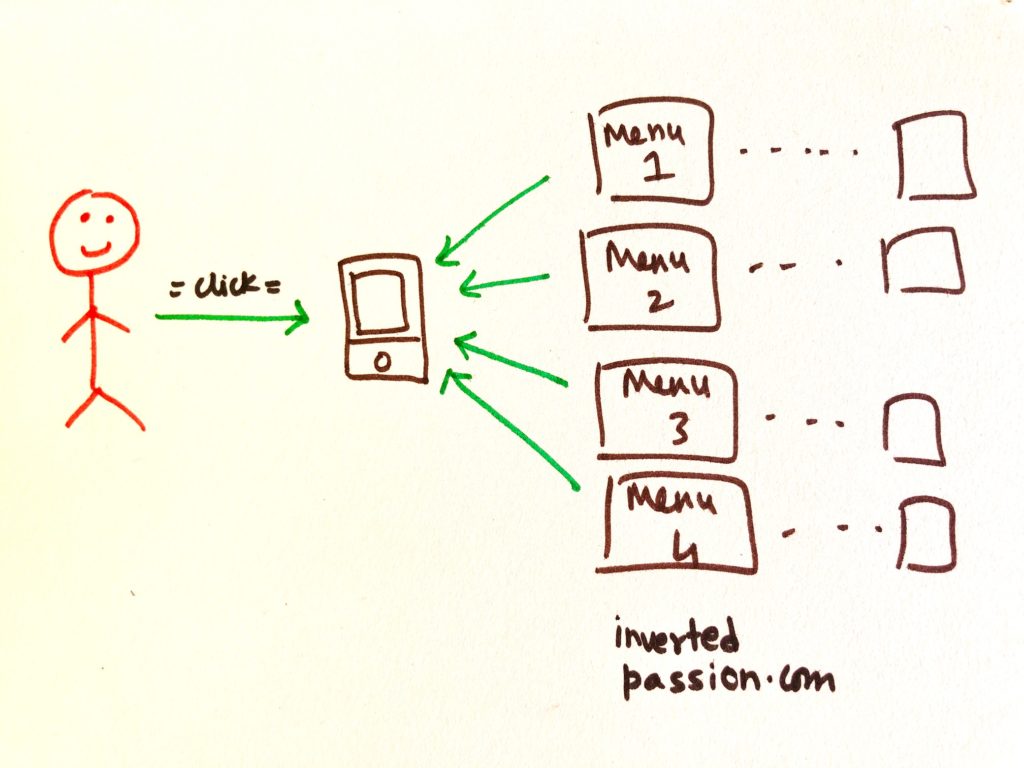

Online food delivery companies attacked all these inefficiencies spectacularly. (They improved over the old way so well that in US there are now multiple online food delivery companies that have IPOed).

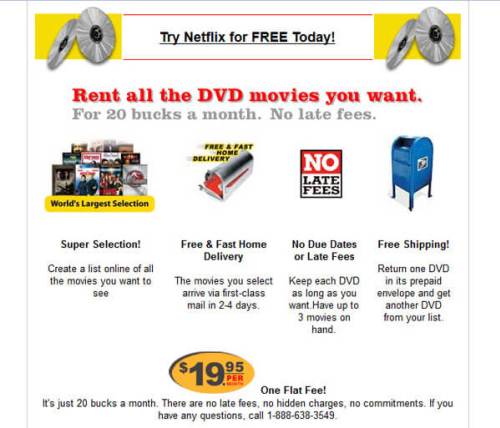

Notice the parallels of the online food delivery model with the original DVD-by-mail model of Netflix. Before Netflix, people had to drive to Blockbuster to rent movies. When Netflix came along, they could now simply choose their options on a website and selected movies were mailed to their home the next day.

What this extra convenience did was to increase the consumption of movies (of course, their flat fee model helped too). Wired in 2002 called this the Netflix effect.

It’s so convenient that the average Netflix customer watches five movies a month. Some subscribers rent twenty or more. (Which is a problem: Netflix loses money on postage for households that rent more than five a month.)

The Netflix effect applies to the online food delivery apps as well. By it so convenient, these apps are expanding the market both by increasing the frequency of ordering and by converting non-customers into customers (people like me who dislike talking on the phone are OK clicking buttons). But this expanding market is a big problem because of negative unit economics.

The cost side of Netflix’s DVD-by-mail business also has a similar structure to food delivery business. (By the way, this DVD-by-mail business still has millions of paying subscribers). There’s two ways to lose money on every DVD that Netflix ships: a) it costs money to physically mail the DVDs; b) they have to shares subscription revenue with studios for newly released titles (revenue sharing ceases after 1 year).

Netflix approached profitability by being creative in their business (gross margins for this business is 50%) and how they did this has lessons for the food delivery business.

From mailing to streaming

First, let’s get this out of the way: unlike movies, food cannot be delivered on the Internet. Netflix knew from the beginning that its future was digital streaming. From the same Wired article (2002):

Today, it can cost more than $30 to send a DVD-quality film over the Internet. As that figure drops, Hastings will consider going digital. “In five to ten years, we’ll have some downloadables as well as DVDs,” he says. “By having both, we’ll offer a full service.”

Now that’s farsightedness and a prediction they got right.

Recommendation system to reduce reliance on hits

Netflix pioneered the model of recommendation system for movies via their CineMatch software. What this recommendation system did was two things: a) it surfaced previously ignored, cheap to acquire but good indie movies and hence reduced propensity of subscribers who wanted to see new releases (an activity that cuts into their profitability because of rev-share agreements); b) it started knowing and recommending what kinds of movies a specific person likes, thereby increasing customer satisfaction (Blockbuster, on the other hand, knew nothing about whether someone liked the movie they rented or not).

In most food delivery apps, there is a similar functionality that allows users to rate the restaurants they’ve ordered from. This helps online food delivery companies do two things:

- a) users start relying on rating and cuisine for food selection, thereby commoditizing restaurants. This slowly tilts the power balance from restaurants to apps and hence enabling food delivery companies to extract higher profits in the value chain

- b) to acquire food and taste preferences of its users and using that to recommend restaurants and give discounts, thereby increasing their customer satisfaction (this is something only an aggregator can do)

For food delivery companies there are two moats that prevent customers switching to competitors. One moat is the habit itself. Every time a user orders food online, she reminds herself how convenient is that particular app (as compared to what she was doing before). And because food ordering is done frequently, this habit gets stronger and stronger until it develops into an automatic reaction: feel hungry -> open the app -> food on the door.

Habits are so powerful that when you don’t get good results on Google, you change your query rather than going to Bing. We change our habits infrequently because we, humans, are loss averse and for a change in habit, we demand benefits that are much higher than what it costs to change (in terms of effort, money or time.) See my previous article for a detailed analysis on cost vs benefits when it comes to making a change.

The second moat is data on my order history and ratings. This data is underutilized but valuable. An upstart food delivery service will have no knowledge about my food preferences. So, in theory, data-enriched features can help me stay with the existing app.

Netflix’s original content strategy

Starting with House of Cards, Netflix in 2013 started investing in original content. The reason they’re producing original content is because they’re able to do it. Before they sign off on a show, they have all the data through ratings and movie watching statistics to know it’ll work. They’ve reduced movie making to a formula. And because they also own relationships with users, Netflix Originals get guaranteed viewership (they send push notifications only for their content + Originals gets its own section in the app). Finally, through ratings and recommendations, they have commoditized movies, so they produce their original content cheaper than studios (they don’t have to spend big money on stars).

After aggregating users, Netflix backward integrated and started making movies. Similarly, food delivery companies are backward integrating and starting their own restaurants and so-called cloud kitchens. Swiggy opened its first private label restaurant this year, Zomato did that last year. This is logical because after reducing restaurants to a commodity, they want to eat the 50-70% gross-margins that these restaurants earn (and they will be able to do a much better job at it because they have aggregated and personalized data on preferences, timing, spending and eating habits people)

This shift in value chain reminds me of what Ben Thomson says in Netflix and The Conservation of Attractive Profits.

It’s not only that Netflix is integrated around the customer experience, it’s that they’re modularized around the content creation as well;

All this is obviously a very narrow prediction about food delivery business that may not pan out the way Netflix is evolving. (And it comes with all the caveats I mentioned before about predicting future.) Still, if anyone is interested I’m willing to make an actual monetary bet (of, say, $100) on two predictions: a) just like Netflix’s recommendations made indie movies famous, the data collected by food delivery companies will give rise to unknown restaurants and dishes rise to fame; b) a major player in food delivery industry will complete its backward integration in next few years (perhaps by acquiring an existing food business or making heavy investments in their privately labeled restaurants).

Ola and FoodPanda

So why did Ola buy FoodPanda? Actually, benefits of this acquisition are hard to see. An acquisition only makes sense if the combination is more than the sum of two entities (what business managers fondly call as “synergies”). I don’t see synergies in this deal. One possible motivation for Ola to buy FoodPanda could be to use its cash in the bank (it raised $1.1Bn this year) to increase revenue so they can come closer to an IPO. There are other explanations but they don’t satisfy much. For example, the acquisition opens an extra use case for Ola’s prepaid wallet (Ola Money). Or, hypothetically this allows cross-seeding of taxis and bikes across two use cases: food delivery or transportation. But none of these reasons are strong enough to warrant acquisition a non-core business.

FoodPanda’s parent company wasn’t too satisfied with India operations and wanted to sell it. So a likely trigger for acquisition could have been that it was cheap and also positions Ola to catch up with whatever Uber does with UberEats (including the possibility of wasting time and resources).

Another reason could be the potential for growth (which again helps with IPO). The food delivery industry is in its infancy (online accounts for 2% of all food deliveries in India). The logic of a large potential upside at a low cost is compelling. However, monetary cost is just one type of cost. In acquisitions, what isn’t generally accounted for (by the market) is the cost of decreased leadership bandwidth on core business, dilution of company culture and increase in the scope of activities that a company does.

What should Ola do with FoodPanda?

Now that you’ve read the article, I have a question for you.

How should food delivery companies (Swiggy, Zomato, etc.) use all the data they have on users ordering and ratings for more customer value?

I'll RT interesting and amusing suggestions.

— Paras Chopra (@paraschopra) December 20, 2017

If you were heading FoodPanda’s business at Ola, what would you do? Tweet your response to me as a reply to this thread and I’ll retweet interesting responses. In the same thread, you can also check out and comment on what others proposed.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra