Good definitions are powerful. Lately, while reading The Art of Game Design, it became clear to me that the author’s definition of games makes a lot of sense. He defines games as problems that people pay to solve with either their time or money.

Unlike movies or books, games are not passive: they require an active participation and in that sense, they’re problems to be solved. And the fact that we willingly pay (with time or money) to solve those problems is fascinating.

Even though I’m not a gamer, I’m building a consumer startup in the behavior change domain and that’s pushing me to study games. Specifically, I’m interested in exploring what is that about great games that people will spend many hundreds of hours trying to master them, while most consumer experiences (including courses purchased or apps installed) have a ~90% churn of users on day 1 itself.

To answer the question of what makes a great game, I read these three books:

Why do we need problems to solve?

In first glance, it feels absurd that we would want more problems to solve. Isn’t life already full of problems?

Yes, but that’s precisely why we’re attracted to games. Because the real life is full of problems, we desire a playground to practice for those problems in a safe environment. And games provide that.

Young ones of almost all animals engage in play. Why? It’s because play allows for simulation of evolutionarily valuable skills in a safe environment. We play and enjoy hide and seek because it helps us practice seeking skills. We play and enjoy chess because it helps us practice thinking and strategizing.

All good games end up feeling good because they help us master a skill that will provide us with survival or reproduction advantage. Games appeal to some of the deepest of our evolved needs. This is why shooting games like Doom or Halo are so popular.

What do we really want?

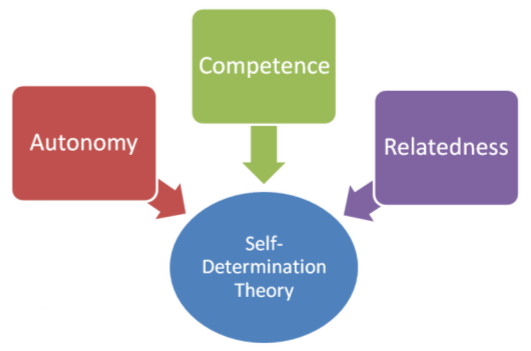

There are many models of what we really want. Maslow’s pyramid is a popular one (which most people know about). A modern and more distilled take on human motivation is what’s known as Self Determination Theory.

It posits that there are three fundamental motivations in all of us.

- Competence: am I good enough? Can I master it? Good games help us gauge how good are we on a particular skill.

- Autonomy: do I have meaningful choices? Can I express myself? Good games give us choices to make that impact how we ultimately fare

- Relatedness: can I belong to a group? Can I get feedback signals of how I stand in that group? Good games help us place ourselves among a group

In short, good games create a narrow simulation of an important aspect of life, and we’re attracted to that because that the safe environment lets us practice and improve our tactics without the dangers of the real world. And that’s why games feel great.

Model of a game

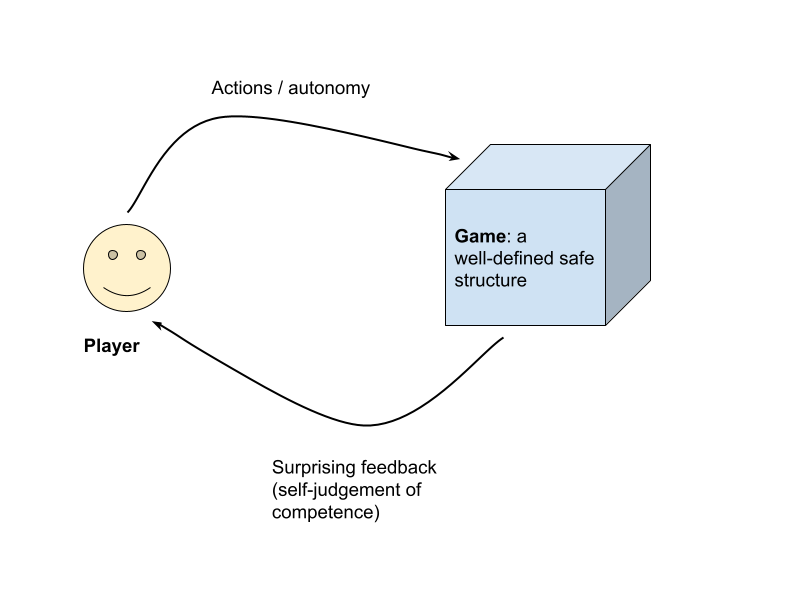

I’m not good at sketching things, here’s a simple visual model of a game to crystallize the theory.

So, the game designer makes a structure with some rules (making it well-defined) and a player actively manipulates it to receive feedback on her competence. Two questions arise:

Why does the player bother?

It’s curiosity about her ability to master the challenges provided by the structure. Since, it is a safe environment, curiosity provides a low-downside, high-upside kind of enticing situation to a player.

What sort of feedback is the player looking for?

Surprising feedback. It’s important that there be uncertainty in the player’s mind about her ability. There’s no value in putting in effort if the answer is already known. That is, if the player knows already knows that she will be able to master or not be able to master, the curiosity dies. The curiosity remains when there’s uncertainty – whether she will be able to master or not. This is why too easy or too difficult games don’t work. A game has to present just the right difficulty level for the player to be interested.

Curiously, this last point of surprising feedback is the core of what makes games fun.

Fun is pleasure with surprises

~Jesse Schell, The Art of Game Design

In fact, our craving for surprises (and variable rewards like those in a slot machine) can be explained by the purported unifying theory of the brain: predictive processing. The idea is that our brain is constantly trying to minimize the error between its prediction of the world and what the world throws up. So, we’re in a way addicted to collecting more information that helps us resolve ambiguity.

Great games present just the right amount of ambiguity about our skill level, and hence we’re attracted to them like bees are attracted to flowers.

So, what makes a great game?

To reiterate, great games create a safe environment to practice a valuable skill and give a sense of winning at regular intervals.

In the real world, we have all sorts of uncertainties about ourselves and the world – am I good at this? Am I better than others at this? How high can I jump? Can I read social cues? Can I strategize a difficult problem?

Games create a safe environment that lets us incrementally reduce our uncertainty about what we are ultimately capable of. This uncertainty reduction (when we win or close to winning) is what gives pleasure.

Uncertainty is important, and that’s why surprises and variable rewards are what make a game fun. If I already have all the information about a specific aspect of me or the world, playing is not fun, but a chore.

This is why it’s boring to play the same levels again and again – the uncertainty is not there all. I know my skill level regarding a level and unless the game is explicitly about beating my high score, it stops being fun.

This is also why multi-player games are fun – they bring an element of surprise and create uncertainty whether my skill is better than the opponent (a deep-rooted drive).

In a multi-player setting, when skill levels mismatch, games become boring. If you’re playing against an opponent (or a level) who is either too good or too bad, there’s no uncertainty. You know you’re going to certainly win or lose, so your interest dies as there’s no uncertainty to resolve.

The best games are well challenged – they keep you on the edge by maximizing your uncertainty because they’re neither too hard, nor too easy. They keep you guessing and rouse your curiosity about your ability. That is why you keep playing.

It’s important to contrast games with game-like systems. Examples of the latter are twitter, Instagram, money, etc. In theory, maximizing the number of followers or likes on social media should be a fun game, but most people report it as stressful. Why?

It’s because in games there are no real-world consequences – they are safe, isolated environments for practicing. But Twitter has real-world consequences. It’s not isolated, so whatever you do on social media ends up impacting your life (how you’re perceived, whether you get a job or not, and so on).

In a good game like Mario, however, whether you win or lose, you have learned the valuable skill of hand-eye co-ordination. The value of games is in the process of playing them, but the value of game-like systems is in their real-world consequences, and that’s why they stop being fun.

A simple example – roller coaster tycoon, is fun because it lets you practice your strategy skills in a safe world. If you lose, you can restart the game. But if you were running an actual theme park with salaries to pay and rider safety to take care of, it suddenly becomes not a game.

Another important aspect of games is simplification of feedback on how you’re doing vs what happens in the real world. If you are job hunting in the real world, what variables impact your chances are mostly invisible. Companies don’t tell you how you could have done better, criteria change company to company. So, you feel less agency. Without agency, nothing is fun, as we’re fundamentally driven to make meaningful choices.

But if there’s a job hunting game with a clear feedback mechanism linking your actions to consequences, it becomes fun because you know you’re controlling outcomes. So, the strategy skill you’re practicing in this game actually matters.

This is why games that are entirely chance based – rock, paper, scissors – start seeming pointless. Gambling is an exception. Blackjack is random, but you feel like you’re guessing patterns and making meaningful choices.

In conclusion, this is what makes a great game

- Simulates a valuable skill

- Provides safe environment

- Clearly defines what winning means

- Maximizes uncertainty for a player by balancing the difficulty level right at the edge

Dive Further

If you’re keen to dive deeper into the subject, see my notes on the book A Theory of Fun.

If you want an abstract take, how about some philosophy of games by C Thi Nguyen:

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra