Is there an arrow of progress in our universe? Or do things change without any particular direction as a goal, like a dust particle engaged in a Brownian motion, bumping and tumbling along randomly?

I don’t think there’s an answer to those two questions. Our thinking is designed to box phenomena into neatly packed categories that capture only a slice of reality. In fact, that’s where the problem with philosophy starts. Even if we both use the same word – say “love”, “free will” or “democracy” – we usually mean slightly different things and these slight differences provide all the fodder for the philosophical debate.

Debates on whether progress exists thrive on similar misunderstandings. People like Matt Ridley and David Deutsch are strong advocates for the idea that there’s an arrow for human progress and that we all have a role to play in terms of pushing it further. They offer historical trends on violence reduction, poverty reduction, and an increase in life expectancy all over the world. Looking from that lens, progress exists. But of course, as you know, there’s no free lunch in the universe so an increase in human lifespan has come at the cost of loss of millions of trees, insects and animals. Looking from the lens of biodiversiry, progress exists – but its direction is reversed. If you ask an environmentalist, they’ll say that things are becoming worse, not better, and point you to the Wikipedia article on the ongoing sixth extinction in the history of Earth.

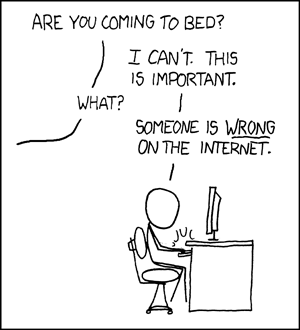

Whether things are getting better or worse, in general, depends on how we define “in general” and nobody takes the pain to define that. This suggests that when it comes to progress, it’s easy to fool oneself and others. All you have to do is to cherry-pick examples that align to your favorite worldview and start shouting that {humans are making things better / humans are making things worse}. You’ll feel great for having a fact-backed point of view on an important question and your opponents on Twitter will feel great about being able to correct someone who’s wrong on the Internet.

Science and logic cannot answer whether progress exists. It can offer us data. How we interpret that data and make it relevant for humans depends on the lens we use. John Gray in his excellent book The Soul of The Marionette suggests that the idea of progress perhaps started with the Christian belief that if humans work hard and get rid of their sins, a heaven on Earth awaits all of us. Paradoxically, science has gradually co-adapted this stance. You can hear it in the optimism that only if we work hard and know more about the world, one day we’ll be able to eliminate cancer or conquer Mars.

John Gray agrees with the fact that, yes, if we work hard we will have the technology to eliminate cancer or conquer Mars. What he disagrees with is how we will use that technology. He says (and I agree) that progress exists in knowledge and technology because these are cumulative. Once a new fact is discovered, you can’t undiscover it. But human morality is different. We’re still shaped by our animal instincts. Just because we have democracy today doesn’t mean that we can’t get dictatorship tomorrow. And that’s why progress doesn’t exist in human morality.

Our technology and knowledge is always value-neutral. The energy contained in an atom can be used to provide cheap energy to millions or it can be used to kill a hundred thousand people. Confusing technology or science progress with moral or spiritual progress is a category error.

The more stakes a question has, the more nuanced one needs to be. And perhaps no other question is philosophically more important to humanity than whether progress exists because it ultimately helps us deal with the question of why we’re here. So, having a definitive answer to the question of progress can help us illuminate how to live life. That is:

- If progress exists and is in the positive direction, we should perhaps spend our life accelerating it. This is what Silicon Valley is hell-bent on doing.

- If progress exists and is in the negative direction, we should perhaps slow it down. This is what the growing Extinction Rebellion is hell-bent on doing.

- If progress doesn’t exist, we should perhaps give up trying to control the world and simply play in the garden. This is what kids in my apartment building are hell-bent on doing.

None of these options work doubtlessly because, as we’ve seen, how we define “progress” dictates whether it exists or not.

So what do we do?

Raising our hands and saying everything is ill-defined and hence ungraspable won’t help. Nobody likes boring-yet-accurate people whose default answer to most questions is “it depends”. Do you think Trump is good or bad for the USA? It depends. Do you think Marvel is better than DC Comics? It depends. Do you think we’re in this universe for a specific reason? It fucking depends on how you define “we”, “universe”, “specific” and “reason”.

Is the challenge limited to a lack of definitions? Does that mean if we’re able to define our terms, we can then use science and logic to guide us on how to live? Actually, no and there are two reasons for that. First, defining an ambiguous term makes it something else. Imagine being asked to define love and your answer is in terms of Oxytocin levels in the body. You will be right by definition (because you’ve defined it), but then you’ll not be talking about love but Oxytocin levels. Clearly, something is amiss.

Similarly, when you define progress as technology progress what you end up studying the dynamics of technology. You see, the category itself changes and perhaps that quells the debate, or perhaps it renders it boring and trivial.

Second, even refinement won’t help because definitions of things are words that require their own definition. By shifting the ball from progress to technology progress, you beg the question: what is technology? There’s no end to how long you can play this game. Philosophers have been doing this for thousands of years and your 2 cents will likely not settle the dust.

So defining progress won’t settle our desire for an answer and our inner violence to deal with it won’t stop.

So what do we do — again?

The easy answer is perhaps what my mom would tell me: why bother? Ignorance is bliss but once you unignore something, you can’t go back to ignoring again. Meditation helps to reduce the anxiety surrounding the lack of definitive answers but, like the Hydra, the question never stops raising itself in your head.

The hard answer is acknowledging ambiguity inherent in the most important questions of life, embracing the fuzziness with both arms, and loving it as if it’s the only thing you’ve got. After making love with the uninterpretable data, perhaps we can begin to question our mode of trying to access answers. I sometimes wonder whether an “answer” to our deepest, unresolved questions aren’t answers at all but are poems, songs, fragrances, or paintings instead.

What if, from time to time, we suspend our desire to master the universe but start allowing it to master us.

To make peace with life, first we need to make peace with ambiguity.

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra