1/ I recently made notes on the book “Hooked” but wasn’t satisfied by the depth of explanation in it.

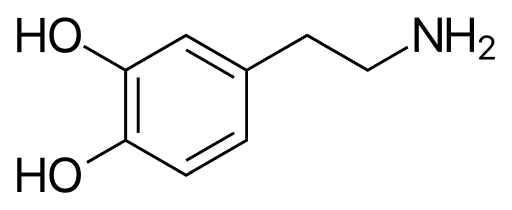

2/ I wanted to get down into neuroscience of habit-forming products and that inevitably lead me to the (in)famous neurotransmitter dopamine.

3/ Before we dive into what dopamine does, let’s first make one thing clear: dopamine does NOT generate pleasurable feelings. (In fact, it is the other way around – pleasurable feelings generate dopamine)

The neural circuits that lead us to “liking” are separate from the circuits that generate “wanting”.

4/ It’s easy to confuse “liking” and “wanting” because they often go together, but they can get disassociated (especially in cases of addictions). Alcoholics want alcohol without liking alcohol.

Here’s a good overview of how “liking” is separate from “wanting”.

5/ If you’re addicted to something, you have an intense desire which fails to resolve into an equally intense pleasure.

It’s not just addictions, this is generally true as well – recall how many times you’ve had an intense desire for something that didn’t live up to its potential. Doesn’t happiness always fall short of expectations?

6/ So, how does “wanting” arise?

In most cases, it is reinforced after “liking”. That is, desire is generated after encountering something rewarding.

8/ This makes evolutionary sense.

Let’s say you’ve tasted something for the first time, and you liked it a lot because it was sweet. Pleasurable feelings evolved with sugar intake because it is full of calories and has survival value (just like sex is pleasurable because evolutionarily it’s beneficial to species). So, “liking” something ends up generating a future desire for “wanting” the same thing again in the future.

9/ The desire for pleasure-generating situations is encoded in the brain via dopamine.

Because dopamine is typically generated after pleasure is felt, it is the “desire” molecule, not the “pleasure” one (as it is commonly mistaken).

10/ Pleasure is not the only way dopamine can be increased.

Many drugs (like cocaine) directly work on increasing activity in the dopamine neural circuits. This means we desire such drugs for their own sake, and that’s why they’re so potent.

11/ Such drugs do give pleasure (initially), but it is hypothesized that it’s because we end up (psychologically) confusing our desire with pleasure. This must be true because over time drug addicts stop deriving pleasure from the drug, yet they can’t stop taking it.

12/ So, how does dopamine work under the hood?

The idea that we desire things we find pleasurable is obvious (and trivial). The more interesting part is that dopamine (and hence desire) is intensified when we get positively surprised.

Let’s break this down as it is the heart of the story.

13/ Animals (including humans) are prediction agents.

We’re constantly trying to make predictions – which way is the water source? Is that ruffling in the grass a lion or just wind? Is that woman interested in me? How much bonus will I get this year? And so on..

14/ There’s always uncertainty in our predictions. Yet, even in the absence of perfect information, we have to take actions.

How do we decide which action to take? What makes one choice more desirable than another?

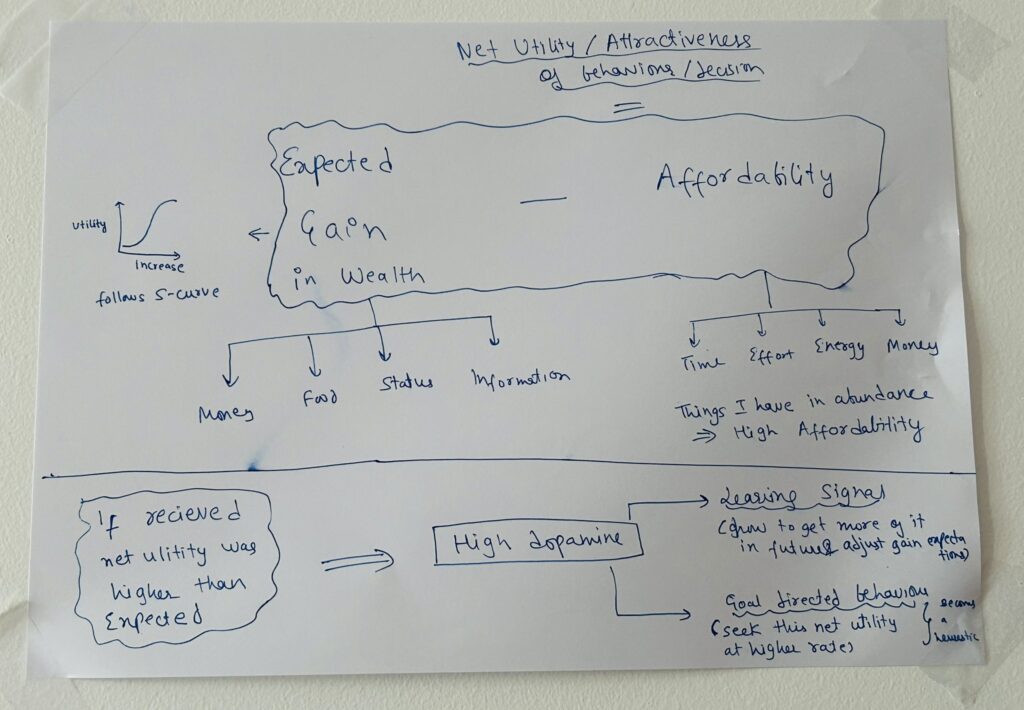

15/ Researchers have found out that our choices follow a remarkable degree of efficiency: we tend to choose an action with the highest expected gain of our wealth.

16/ The entire field of neuroeconomics explores the question of how efficient is our decision-making. I will explore the topic in the next essay [subscribe for email updates, if interested].

There are obviously tons of nuances in this. But, for now, it should suffice to imagine that our brain is constantly betting: which choice can lead to the highest gain for the minimum investment.

17/ Brain has expectations of outcomes for various choices it is making (consciously or subconsciously). If I eat this, I expect that. If I go south, I may find water. But if I go north, I may find nothing.

18/ Now, when these bets by the brain are resolved, and we get to know actual outcomes, dopamine serves as a signal for a) whether the outcome was better or worse than expected; and b) how much better (or worse) was the outcome than expected.

19/ In nutshell, the brain is a prediction machine for rewards (I do this -> I get this) and dopamine represents errors in predicting rewards.

So, think of dopamine as a signal to the brain to try to learn from surprising information.

19/ This difference in expectation of rewards and what is actually resolved is called a reward prediction error, and dopamine activity codes for that. Higher the surprise, higher the reward prediction error, higher the activity of dopamine neurons.

20/ Dopamine generating neurons are widely connected to multiple networks in the brain. Mostly, dopamine induces the following downstream activities:

- Attractiveness (of reward): dopamine helps in learning by adjusting the expected reward to be closer to the actual reward, so that next time cost-benefit calculations have less error. This is why the music that sounded strange the first time starts sounding a little better the next time. Our brain is getting better at predicting what’s rewarding.

- Automaticity (of decision): since decision-making is energetically expensive, it makes sense for rewarding behaviors to become habitual and automatic over time. Neuroplasticity literally ensures frequently rewarded behaviors become more and more efficient (and hence automatic over time). This is why, once spotted, you’re unable to stop yourself from opening that bag of chips.

- Exploration (for even more reward): a better-than-expected reward suggests a gap in knowledge, so the animal is not just satisfied with the reward but also desires to be able to know how rewards are generated in the environment. Information about a reward is (almost) as valuable as the reward itself, so (safe) exploration of the environment producing intermittent rewards makes sense. This is why we can’t stop checking social media feeds, as it’s impossible to predict when and how we get socially valuable rewards in it, so the brain remains hooked.

21/ In different dopamine primers, you’ll read that dopamine is implicated in different functions. The reality is that it triggers many of the adaptive behaviors of learning, exploration and automaticity.

22/ Why do we get bored with things that we once enjoyed? Blame dopamine for it.

If you were expecting a reward and get exactly that, your brain doesn’t increase dopamine production. That’s because there’s no point in optimizing things even further, since you got what you were expecting. No further learning, exploration or automaticity is needed.

23/ For example, if you were exploring how to tell if an oasis is nearby, once you’ve figured out an answer (perhaps it is the color of nearby soil), there’s no further utility in spending your spare time in exploring. Your desire (and curiosity) is gone (yet the pleasure of eating fruits still remains).

24/ Desire (to explore/try/want) is generated when learning is incomplete. If a lab rat gets sweet juice each time he presses a lever, it learns pretty quickly that the next time it needs sweet juice, it can press the lever. But it stops pressing the lever because it doesn’t need sweet juice all the time. (The body is adapted to avoid too much of a good thing).

25/ But if the same lab rate gets sweet juice probabilistically, the learning never completes. It keeps trying to press the lever to figure out factors that predict sweet juice. The gap in knowledge about the reward generating process is intensely motivating. Is it that pressing from the top does it? Is it the speed of pressing? Or is it the shadow? Or the yellow light? And so on.

26/ Slot machines exploit this tendency by creating conditions where “near misses” frequently occur. The brain goes crazy in those situations, since the gap between a reward and what you got is so less than it’s worth trying again. (Maybe this time you’ll get the reward or less how to get one).

27/ So, the desire for an action is generated by both: the desire for efficient acquisition of rewards and the desire to learn (how rewards are generated).

28/ You can imagine dopamine as signalling the value of work.

That is, the higher the dopamine produced, the more it makes sense to put in effort towards an action: either the reward will be worth it, or the information gained will make up for the effort.

29/ Consider how all classic high-dopamine activities are low-effort, high-reward situations: opening the freezer and finding your favorite ice-cream, opening Instagram and discovering 100 likes, an unexpected bonus from your work.

30/ It’s interesting to note that we actively seek high-dopamine producing situations. Why are we addicted to social media feeds or actively plan to go to a bar with friends and gossip?

We seek dopamine hits. Why would that be?

31/ There could be an evolutionary advantage to seeking positive prediction errors, i.e. situations that have the potential to give us larger than expected rewards.

This is because by active exploration of what we don’t know, we end up learning more and more about where rewards exist in the environment. Our ancestors who exhibited behaviors that generated extra dopamine survived better, and this is why we seek dopamine generating situations. (This is also why we’re addicted to seeking dopamine hits such as social media feed or going to a bar with friends).

32/ The way dopamine works also explains why we so easily spring back from failures.

That’s because of this interesting nuance: if rewards are worse than expected, dopamine doesn’t reduce as much.

33/ The implication of this is that we DON’T mind occasional lack of expected rewards as long as we get unexpected rewards.

This is why we’re okay with wasting hours on social media feeds as long as occasionally we find a banger of a tweet that we find extremely rewarding.

34/ Let’s switch gears and talk about how to apply this knowledge about dopamine for product design.

35/ For me, the TLDR is this:

If you model the user as a sequence of attention-spans, your job is to create a trail of surprising rewards for her to follow.

Anticipate what she’s expecting the next moment (which could be “I have no idea” initially), then exceed those expectations in terms of rewarding experiences.

36/ With most products, after the initial burst of novelty, users form a good predictive model of interaction and thus their desire to explore further diminishes. This is fine for functional products (like Uber or a hammer) as they’re used as a utility, and not an end in itself.

But even for tools, a positive surprise can re-kindle desire for the product. Remember Uber Cats? They certainly did understand a thing or two about dopamine.

37/ For many consumer products, however, where retention and time-in-a-day are the key metrics, it’s essential that surprising reward never end.

Social media is a source of endless surprising rewards (containing valuable information and social signals), and that’s why Facebook/Instagram/WhatsApp are giants.

38/ For video games, dopamine’s behavior suggests that continuing to unseat expectations is the key job. Tic-tac-toe stops being fun once you figure out how to win it.

39/ Dopamine’s impact on our behavior unifies many insights I’ve come across lately.

40/ Let’s start with a definition of fun.

Fun is pleasure with surprises.

41/ Games are problems people pay to solve.

42/ We love stories because they’re partial puzzles for our brain to solve.

43/ Thrillers thrive because they tease us with an answer, but then go beyond by delivering something totally unexpected.

44/ How about explaining what I heard about how mobile games should be marketed (subvert expectations)

45/ Plus, why everything looks the same now.

Hint: that’s because before beating expectations, you have to meet them.

46/ Before we conclude, three important nuances for products: because expectations are set in the mind of the consumer, exceeding it often involves beating the standard set by other products.

So, if you have an app in the app store, people expect an app of certain quality and matching it isn’t enough. Remember: desire is generated by surprising rewards. So, the job becomes tougher: you have to beat those expectations by exceeding the quality expectations your users have (in pleasantly surprising ways).

47/ The second nuance: you can’t wait too long to tease and dole out rewards. Unlike a lab rat where the only source of rewards is the lever you have in the cage, users have infinite sources of potential rewards (hello TikTok!). They expect rewards to frequently occur in the apps/products they use and if they have to wait long enough, that is a negative surprise and that increases their desire to be away from your app.

32/ The third nuance is that we find it joyful to put in (some) effort to figure out a reward. We spend time reading a story, watching a movie or playing a game. It’s no fun to be told you won without doing anything. Just getting a reward without effort isn’t enough, as it has no predictive value and we have no idea what to do in the future in order to get a reward.

So, make users work for a reward, but not too much. (Now you know why TikTok has a swipe up gesture and not autoplay!) Reward has to be always much higher than the effort put in (otherwise, as optimal foraging theory predicts, people will give up and explore somewhere else).

32/ TLDR:

Desire is generated when we are repeatedly teased with something valuable, work a little bit to resolve it, and discover something even more valuable than we expected.

I have put this on my wall to remind myself how desire is generated. You might want to do the same 🙂

Join 200k followers

Follow @paraschopra